Introduction

Last month I had the privilege of presenting the topic of The Tay Bridge Disaster at a PMI Houston chapter meeting.

In preparing for the presentation several new ideas occurred to me.

Also, during the Q&A other points were raised.

I therefore decided to take another look at the topic.

The overall story is covered in earlier posts Part 1 (Here) and Part 2 (Here).

This post assumes that knowledge or that you attended last month’s presentation. (If not, you should read Parts 1 & 2 before proceeding)

First, a little Luck

The Tay bridge disaster and probably any such tragedy produces examples of lucky escapes. I did not cover them in the earlier posts so here are two examples.

There are several accounts of people who should have been on the train but through good fortune were not.

David Swinfen ends his book The Fall of the Tay Bridge with the tale of William Brown.

William, a six-year-old boy, was due to visit his uncle in Leuchars with his grandmother and sister Elisabeth, who both died in the disaster.

However, William had been a bad boy, and as we would say today had been grounded.

He ends his account:

“… my life was saved by being a naughty boy, for which I thank God.”

An even closer escape was that of a Mr. Linskill, of St. Andrews, who was due to leave the train at Leuchars. (Where William’s Grandmother and sister joined the train).

He had arranged for a carriage to meet him at the station. But when it did not arrive, he reboarded the train with the intention of spending the night in Dundee and returning home in the morning. Just as the train was about to leave his carriage arrived, and he lived.

We do not have any trouble recognizing these as random lucky events.

But as project managers we tend to discount luck unless it is bad. We then attribute our success to our stellar abilities, and not as is often the case luck.

As Nassim Nicholas Taleb indicates in the title of his book, we are “Fooled by Randomness”.

It is important when we perform a Lessons Learned Review, that we fully acknowledge when we were lucky. Luck is covered in more detail in the blog post “Better Lucky than Good” (Here)

Question #1 from Patricia

What do you do if you are not allowed to choose team? You have to use the resources assigned.

Answer #1:

I believe we have to accept this situation as inevitable, and that we are unlikely to get to choose everyone that we want. Often when we are assigned staff, who may not be our first choice, they are competent and can accomplish the project tasks. Not all tasks are equal and for many this will be sufficient.

However, some tasks/roles are critical

Staffing decisions can be viewed in a similar way to the engineering choices made in answer #4b.

Does this person weaken or strengthen the project?

- Choose your battles – fight for the positions that matter

- Coach where necessary (Coaching can be delegated)

- Encourage without micro-managing

- Remember, a well-coordinated team of average players can often outperform a group of stars. (See Chasing Stars by Boris Groysberg)

Question #2 from Arman:

Great presentation Jim! Question: wasn’t the turnover/commission process flawed as well? It seems that more observation and trial runs should have been required

Answer #2:

Yes, clearly there was a lack of process or attention with regards to turnover, and poor Henry Noble was left with the task of maintaining the bridge with little experience, or resources and no guidance.

With regards to observations, there were numerous compromises to the design, the implications of which do not appear to have been fully considered, so it is likely that the designer and builder saw what they wanted to see. (Also see Question #3 below)

With regards to General Hutcheson of the Board of Trade he did perform multiple and increasing load tests and measured deflections of the bridge. One must assume they were satisfactory. Also, the reports of slack and chattering bracing members that Noble and others reported at the Inquiry, were probably not apparent on the pristine newly painted bridge.

Question #3 From Edgardo

Great presentation. Q: Was there not a quality control post build? Maybe not done at the time?

Answer #3:

I believe the answer is no.

Decisions had been made earlier and were not revisited post build.

The bridge was standing therefore everything was good.

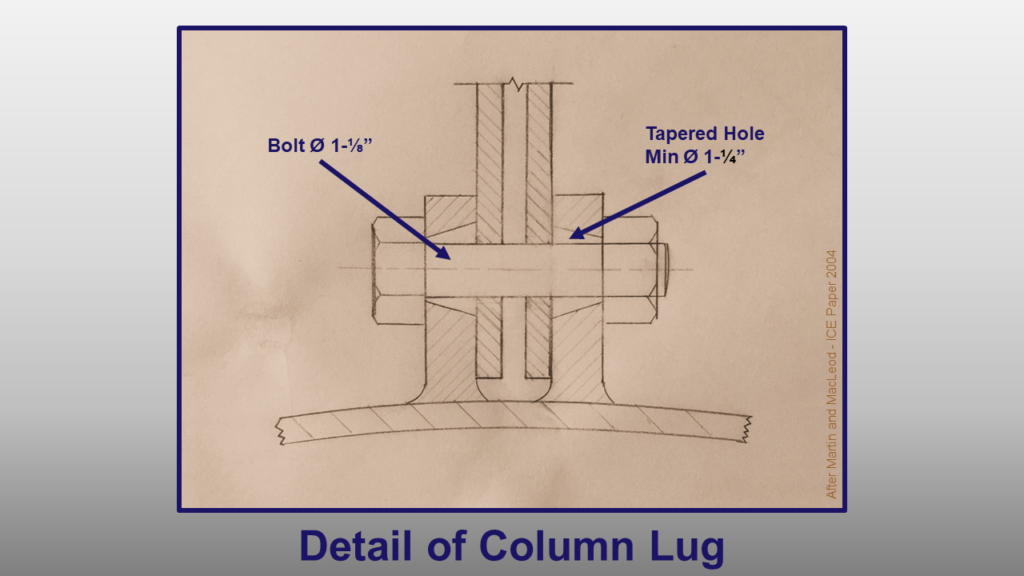

This is what Diane Vaughan called “Normalization of Deviation”1. For example, the decision not to bore out the lugs and use undersized bolts was contrary to good engineering practice. But Bouch and the team had normalized this in their minds and therefore had no need to revisit it.

Also, by then it was too late to do anything about it. (As far as I know every lug on the columns had the same issue)

Question #4: from George

Are there any systems or methods you might recommend to vet decisions during a project to prevent such faults?

Answer #4a:

An approach, and one that will also support Answer #4b is the concept of “Giving Voice to Values”2, developed by Mary Gentile.

This is a way to enhance your ability to make correct moral and ethical decisions.

Now you may argue that the decisions Bouch made were not moral but technical and fiscal. They were not. They were moral compromises. Bouch knew how to design, witness the Deepdale and Belah viaducts which stood for over 100 years.

He compromised his ethical duty to ensure the safety of the public for budgetary reasons.

The Giving Voice to Values is covered in the Ethics Part 2 post. (Here).

The system assumes that you will be asked or tempted to take ethically questionable actions at some point during your career.

If you are unprepared when confronted, you will be more likely to compromise your moral values.

However, if you have a clearly defined and constantly articulated values set, confronting, and resisting that request or temptation will be much easier.

It is also important to define the Project Exit Criteria at an early stage in the project.

Under what circumstances will you “pull the plug”?

If you are prepared and clear on the criteria it is much easier to make the decision to cancel the project.

However, in a major infrastructure project such as the Tay Bridge it is much less likely that the project will be cancelled, but there will be a need to find additional funds. If the project cannot be safely executed due to budget restrictions, then it is up to the manager to Give Voice to Values and leave the project.

Interestingly at one point during the project when the bridge was completed but not fully tested, Bouch was asked to allow trains working on another part of the network to cross the bridge. He refused and said if overruled he would resign. However, as we saw he was blind to other compromises he made.

Answer #4b:

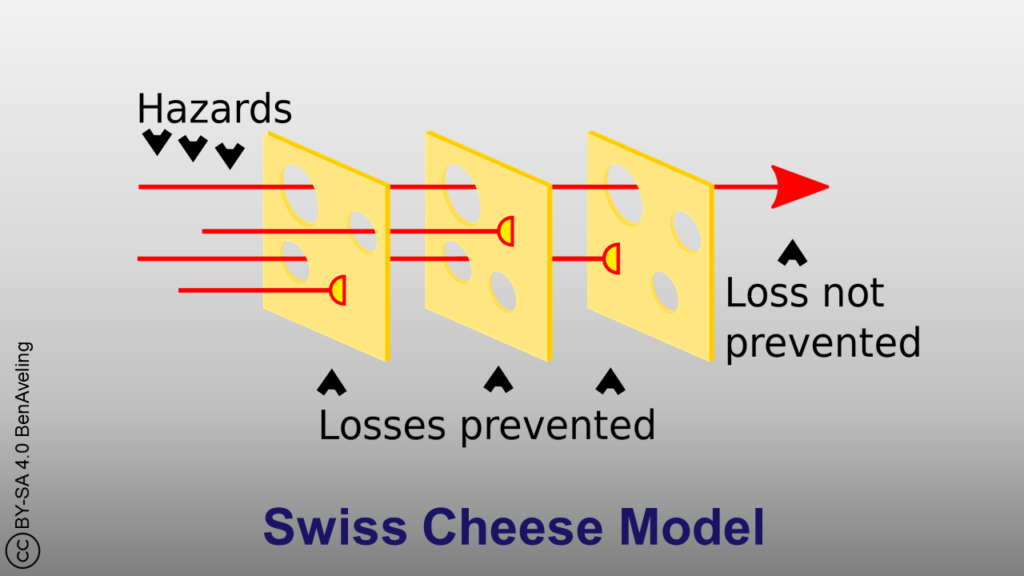

I mentioned the Swiss cheese model, developed by James T. Reason, during the live Q&A and will expand a little on it here.

This model is usually used to review safety systems like those used in nuclear reactors, to ensure that there are safety measures inserted to prevent disasters.

However, in this case we can use the concept to assess if the various cost saving measures compromised the design by compounding each other.

Due to the foundation problems Bouch and his team were forced into a major design change.

He went with something he knew well and replaced the brick columns with braced iron columns. This was the concept used on the Belah and Deepdale viaducts. However, the Tay Bridge columns had a much narrower base which resulted in a flimsy look and a very high centre of gravity.

Given those limitations it would have been logical to ask the following question each time a subsequent decision was made:

Does this choice weaken or strengthen the design?

As can be seen from the animation above each choice made for purely economic reasons, (as admitted by Bouch at the Inquiry), potentially weakened the design, and contributed to the final disaster.

But was he limited to the narrow footprint?

Clearly not, as is apparent when one views the current bridge with its wider footprint.

If this occurred to Bouch’s team then cost likely drove the decision not to go that route because it would have required two caissons for each column.

Another option would be to use a “Red Team” to analyse the problems and formulate a safe and practical solution to the foundation problem. Although red teaming was not a known concept in the 1870s, the team that designed and built the second bridge were able to solve the problems and build a bridge that is still functional over a century later. (To be fair they did have the benefit of hindsight and a much-chastened customer willing to spend more money)

Red Teaming3 is something that requires a post to itself, but a brief description is as follows.

Red teaming is a concept used by the military, during exercises and planning, the Red Team represents the enemy, and their aim is to circumvent the plans of your team, usually designated Blue Team.

This concept has been incorporated into business strategic planning and cybersecurity.

I have found little in the project management literature on the use of the concept, but I see no reason why it should not be used successfully in our field.

The advantage a red team brings is that it avoids the cognitive biases and group think of the main organization and can provide solutions that the conventional approach fails to see.

The red team can be external consultants or personnel from inside the organisation.

Thoughts on choosing the Team Members:

- Must be enough of an insider to understand the technical problems

- Must be enough of an outsider to think independently

- Normally young and lower rank/status in the organisation

- Often mavericks

Next time your project runs into a major problem Red Team it.

Answer Summary:

Options as outlined above are as follows:

- Long-Term cultural options

- Develop a values culture

- Set project exit criteria early

- Change Options

- Use a Swiss Cheese Model to question choices

- Red Team the problem

Question #5: from Pam

Great presentation! many projects I work or have cost pressures similar to this project, especially with COVID cost increases and projects approved before those increases – pressure to still deliver on previously approved budgets. have you experienced similar cost increases and what were options you looked at?

Answer #5:

Like staffing choices financial constraints are an inevitable factor in the life of a project manager.

A key expectation of the project manager is to bring the project in on or under budget.

Of course, this is often easier said than done in an uncertain world, but equally you do not want to increase the budget for every bump in the road.

Crisis like Covid often bring cost increases, but they may also bring potential savings. For example, your material and transport costs may rise, but if you have a project with a sizable travel budget, (which you now cannot spend) this can be repurposed to offset the cost increases.

If the question is the wage bill, several organizations have solved this problem with voluntary wage cuts to allow the retention of all staff. This should also reduce the overhead.

If the project is an internal one it may be possible to reduce the scope of the project. This is not an option for all projects, we saw what happened when they cut costs on the Tay bridge.

If cost reduction will result in reduced quality and safety, then this is where Giving Voice to Values comes in and you argue the case for the additional funds.

A very strong argument is that if we do not have the time or the money to do it right, we will invariably have to do it twice.

The approximate costs for The North British Railway Company were as follows:4

Estimate for the first Bridge: £217,000

Cost for the first bridge: £350,000

Cost for the second bridge: £640,000

Cost for approach works: £ 16,000

TOTAL COST: £1,223,000

As can be seen it cost NBRC much more than if they had built a two-track bridge to the correct standard the first time and 59 people would not have lost their lives.

If ordered to proceed down the cheap path you then need to make a moral decision and ask yourself:

“Is the safety compromise something I can live with?”

Or, if it is not a safety but a quality/functionality issue:

“Do I want my reputation defined by this?”

I appreciate this is an even harder decision during the Covid crisis than in a normal market where jobs are more easily available.

Finally, there is always humour.

In one place I worked we got a new general manager who was intent on a cost saving drive. We had all gone through the oil industry down cycles, but this was during the good times, and some of the cuts were petty.

One member of staff (not me) frustrated with the pettiness removed all the toilet rolls in the bathrooms and replaced them with this:

I don’t know that it did any good, but it did lift the spirits.

What happened? – Final Thoughts.

Did Bouch just run out of luck or are there other explanations for his shift from apparently successful engineer to total failure?

Following the disaster, Bouch’s career was examined, with that 20/20 hindsight, and there was evidence of similar practices, but he was lucky, and the previous projects were successful and so was he.

Henry Petroski in his book, To Forgive Design – Understanding Failure, postulates that had the Titanic been lucky enough to miss the iceberg, she may have continued for years to steam the Atlantic her illusion of unsinkability intact. The inherent design flaws would never have been highlighted.

We looked at some options, open to modern managers, to avoid the same fate in the Q&A section.

From what I have learned about him he was a decent man, who stood by his staff and made no effort to deflect the blame.

Had he been an evil or callous individual, he could simply have walked away from the failure, but as well as destroying his reputation it destroyed his health and he was dead withing months of the Inquiry.

So! What prompted him to act the way he did?

Prospect Theory

Kahneman and Tversky developed Prospect Theory, which states that an individual when in a Domain of Gains will tend to be more risk averse. However, when in a Domain of Losses will tend to be more risk seeking.

Following the discovery of the foundation problem and the forced redesign Bouch was thrust into a Domain of Losses.

- Loss of reputation

- Loss of a dream

- Financial loss

- Escalating costs

- Pressure from the client

He deviated from his successful Belah and Deepdale viaduct designs as he scrambled to stem the potential outflow of cash.

He fooled himself that each small change was insignificant, but together they led to tragedy.

Be aware of which domain you are in and use some of the techniques above to mitigate your risks.

Step-back and think!

There but for the grace of God go I

This was an expression of humility often used by my mother.

We tend to look at Bouch and think that we would never fall into the same trap, but in the words of Richard Feynman it is all too easy.

NOTES

1The concept is detailed in her book “The Challenger Launch Decision”

2Giving Voice to Values

3See Bibliography below for more information

4From an extract of the book – Fife Pictorial & Historical: Vol. II – A H Millar

Reproduced on – The Newport, Wormit & Forgan Archive

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- The Fall of the Tay Bridge – David Swinfen

- The Challenger Launch Decision – Diane Vaughan

- Giving Voice to Values – Mary Gentile

- Fooled By Randomness –Nassim Nicholas Taleb

- Red Teaming – Micah Zenko

- Red Teaming – Bryce G. Hoffman

- Chasing Stars – Boris Groysberg

- The Newport, Wormit & Forgan Archive (Here)

- To Forgive Design – Understanding Failure – Henry Petroski

What a great read. I really like the questions and answers format. I learned a lot about what went wrong with the Tay Bridge. Certainly that when values are not clear, we are not able to stand firm at times of crisis. Giving Voice to Values is a great book and is part of my library.

Thank you Mari for the feedback

I want to express my gratitude to Jim for stepping in to be a speaker at the Project Management Institute Houston Chapter (PMIH) University of Houston Student Venue! Although The Tay Bridge disaster happened in 1879, it is evident that these kinds of mistakes and failures can still occur nowadays. The main lesson learned from this presentation was that as a Project Manager you have to always be realistic. Unfortunately, sometimes we don’t tolerate overconfidence in others but we indulge in it ourselves (Richard Feynman). I do agree that effective leadership requires confidence. But it is possible to be overconfident, especially if you’re in a position of authority. Misplacing our confidence can lead to catastrophe as was mentioned in the presentation. Knowing the difference between true confidence and false confidence, then, is almost as important as having confidence in the first place.

Thank-you, Zara. – It was my pleasure