Introduction

On the evening of the 28th of December 1879, a violent storm brought down a section of the new Tay rail bridge, taking with it the Edinburgh train, killing all onboard.

The Nation was in shock, but Viscount Sandon, The President of the Board of Trade, wasted no time in opening a Court of Inquiry into the disaster.

There were three members:

- Chairman: Henry Rothery (Commissioner of Wrecks)

- Col. William Yolland (Chief Inspector of Railways)

- Willian H. Barlow (Professional Engineer)

The members travelled to Dundee and opened the Inquiry on Saturday 3rd of January 1880, continuing on the 5th and 6th.

During these three days they visited the site and heard testimony from numerous witnesses.

As well as the Court there were also three principle interested parties, who as we would say today “lawyered-up”.

- The Board of Trade

- The North British Railway Company (N.B.R.C.)

- Sir Thomas Bouch

The Initial Evidence

The Court heard from the various employees of the N.B.R.C., including John Watt and Thomas Barclay who we met at the opening of the previous post.

None of them had actually witnessed the disaster and could only provide background information.

Various other individual testified to the severity of the storm describing the damage to building and monument in and around Dundee.

All indicated it was the worst storm in living memory.

Testimony was taken from the salvage workers including the divers.

Further detailed information would have to await further analysis of the wreckage, and the Court was adjourned on the 6th of January.

The Search for Witnesses

During the break in proceeding all interested parties sought witnesses who would support their case, when the hearings resumed.

The Court Reconvenes

The Court reconvened in London on the 26th of February and started hearing testimony.1

The first topic was the claim by a former Lord Provost2 of Dundee that the trains travelled at speed well over the recommended 25mph and would often race the ferry.

This was reported to have caused severe oscillations which it was speculated may have led to structural instability.

The company called several rebuttal witnesses including numerous drivers who denied the claim.

Next was a review of the Wormit Foundry, which was damming.

David Swinfen tells us that the foundry foreman, Fergus Ferguson, made the mistake of telling the Court Chairman, “if I tried to explain it to you without you being a practical man you could never understand it”

He then proceeded to show himself to be unprofessional and incompetent.

It became clear that there was a total lack of quality control, from low quality materials to poor workmanship. There was also widespread use of filler to hide flaws in the casting.

Ferguson left the Inquiry with no credibility.

The Inquiry next looked at maintenance, where they again heard tales of oscillations when trains crossed the bridge. Painters and workmen told of bolt heads and bolts being found and not knowing if they had fallen or been left during construction.

Henry Noble had been appointed by Bouch, who had a contract to oversee the maintenance of the bridge, as maintenance supervisor.

Noble had originally joined the project as an inspector of the brickwork columns.

He was now responsible for everything apart from the train track.

He was a very conscientious man but was totally lacking in the experience to cope with the structural problems which became evident.

At one point he noted that some of the column ties had come loose and purchased metal with his own money to make wedges to take up the slack. This may well have made a bad situation worse.

Noble was certainly not qualified for his current job, however he was honest and conscientious, but that was not enough. He had been placed in an impossible position.

The Court heard from a number of experts regarding the winds in the Tay estuary.

First was Sir George Airy, The Astronomer Royal. (He had previously been consulted by Bouch and had advised that there was no need to consider wind loading in the design).

Despite his playing down the effects of the wind, other experts testified that the high wind loadings could be expected in the area of the bridge, and that they would act on large areas of the bridge simultaneously.

It is somewhat strange that British engineers did not take account of wind loading, since it was common to do so in both the USA and France. It was a hard lesson and they would on future projects.

Finally, Bouch was called and spent around 12 hours under questioning.

He vigorously defended his design and the members of his team. To his credit he also accepted full responsibility and at no time attempted to deflect blame on to his subordinates.

Despite a spirited defense, his reputation was destroyed.

In addition to the witnesses called, a number of the columns and the tie bars were sent for testing and all were found to fail well below the design and material limits.

The column lugs, where the tie bars were secured, failed at around 30% of the materials rated load. This was probably due to the fact that the bolt holes were cast, rather than bored, and were tapered, causing the load to be transferred to only a small area of the lug.3

The Final Report

Bizarrely there were two final reports, one from the two engineers, Yolland and Barlow, and a minority report by Rothery.

Both generally agreed on the causes of the disaster, but Rothery’ s report went further in assigning blame.

During the Inquiry Bouch had made the case that the bridge was brought down by one or more carriages striking the bridge, but neither report accepted that hypothesis.

The reports were presented to Parliament in June, and concluded the following:

- The gale force winds brought down the bridge.

- This was exacerbated by:

- Design limitations

- Substandard materials

- Poor maintenance

- The stresses introduced by the train entering the high girders at the height of the storm, may have precipitated the final failure.

Bouch was blamed for his failures of design, and management during construction and subsequent maintenance.

His health quickly deteriorated, and he died 4 months after the Inquiery Report was presented to Parliament.

Modern Theories

There have been several modern postmortems on the disaster, but I will take a brief look at only two.

The first was the result of computer analysis by Tom Martin and Ian MacLeod published in 1995, which concludes that the bridge blew down.4

The second by Peter Lewis and Ken Reynolds published in 20025, contends that the failure was due to metal fatigue, which was not something understood by Victorian engineers. They believe that the oscillations reported by many contemporary observers caused fatigue in the lugs and that the bridge would have failed without the storm.

Martin and MacLeod published a rebuttal in 20046

They contend that there would not have been sufficient wear cycles during the life of the bridge to cause fatigue and maintain their original hypothesis that the wind brought the bridge down.

I have referenced the papers below so you can read the details and make up your own mind

Conclusion

There is no doubt that the storm brought down the bridge and that there was clearly a myriad extenuating circumstances, but what was the real reason?

Let’s try to do a 5 Why exercise:

- Why did the Tay bridge collapse? It was blown down in a severe storm

- Why? There were design and manufacturing defects.

- Why? The Engineer was trying to cut costs.

- Why? He had a reputation for delivering cheap

- Why? Because this was what the railway companies wanted.

Essentially the company employed the First Little Piggie, because he was cheap and predictably the Big Bad Wolf, “huffed and puffed and blew down their bridge of straw.”

The North British Railway company may have failed to note the moral of The Three Little Pigs story, but they did recognize the Goose that laid the golden eggs.

As was detailed in the last post the bridge improved the Company’s profitability, customer share, stock value and was commercially a big success, despite the ultimate tragedy

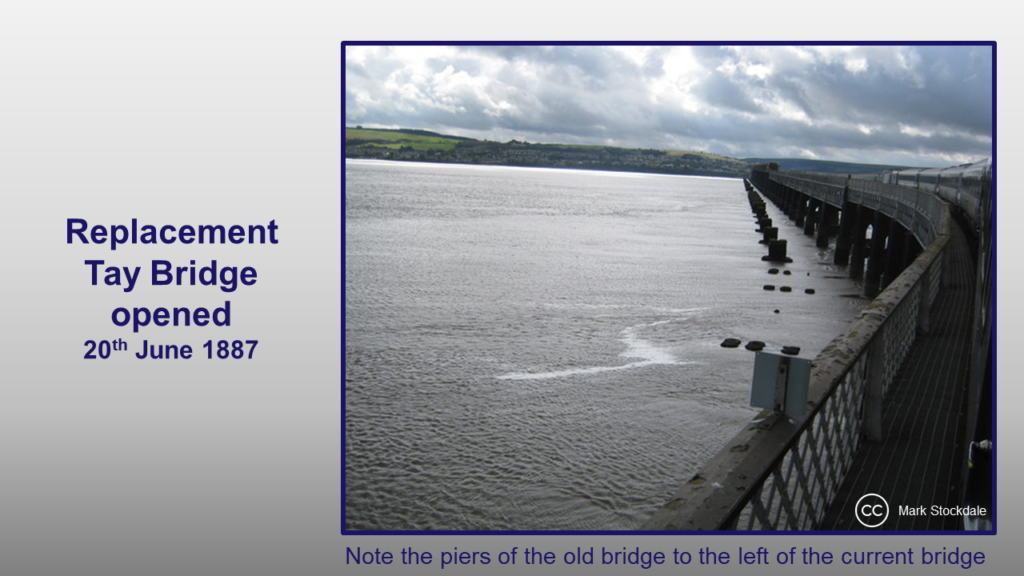

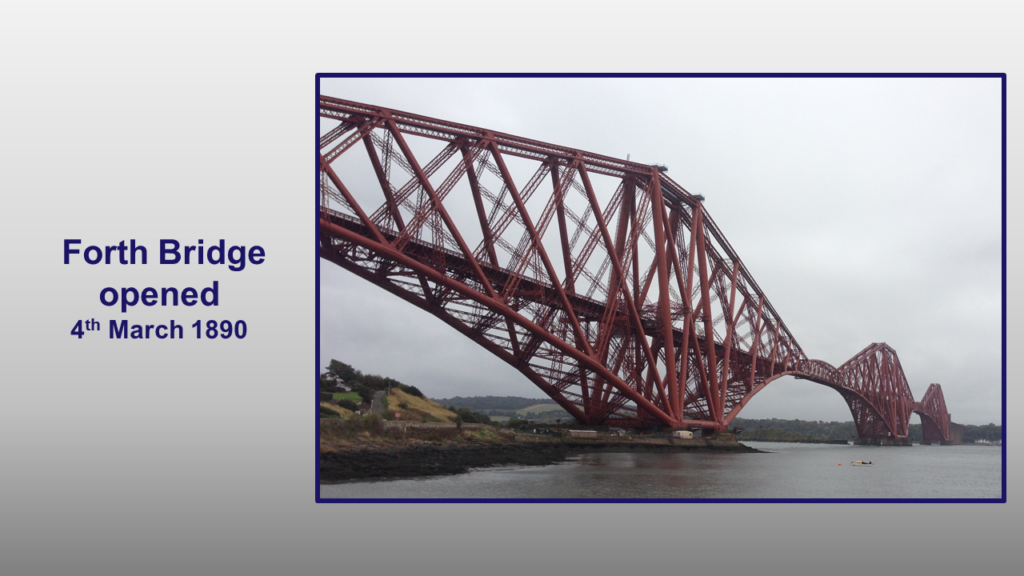

Having dispensed with the services of Bouch, they immediately embarked on planning for a replacement Tay bridge, and a new Forth Bridge.

Both were ultimately built by the highly reputable William Arrol Company, who also went on to build Tower Bridge in London.

The Forth Bridge benefited from all the lessons learned on the first Tay Bridge and will be covered in detail in a later post, when we will look at how a bridge should be built.

Both have stood the test of time and today still carry many trains a day.

Top Lesson for Project Managers

As outlined above there were multiple physical reasons for the disaster, but ultimately, they can all be traced back to the fact that there were systemic management and cultural failures.

- Over confidence

- Poor design choices

- Poor management and supervision

- Poor staff selection

- Poor manufacturing control

- Poor maintenance

Over confidence

Victorian engineering was at its height and was overflowing with confidence and hubris, anything was possible, nature could be tamed.

But, as the saying goes “Pride comes before a fall”, and it was a painful fall.

Bouch had sought advice regarding the required allowances for wind loading and was blithely told it was not a factor he need consider. (Indeed, by some of people who would later judge him)

He happily took the cheaper options, which pleased his clients.

Poor design choices

When questioned on a number of items during the Inquiry Bouch responded that the decision was made for reason of economy.

It is ethically incumbent for a project manager or professional engineer to make judgements based on the overall functionality and the safety of the end users of a product, and not on satisfying the client’s financial constraints.

This I appreciate is a difficult balance to maintain, and in the case of the bridge there was no single factor. Cost saving in one area may not have led to disaster, but together they led to failure.

The single-track design led to a flimsier structure.

This may not have been a problem had foundation issues not led to the replacement of the brick with iron columns.

- Version 1 of the iron columns had 8 tubes

- The final version was reduced to 6 tubes (To reduce the load on the foundations)

- Although similar to the Belah viaduct, from the photographs, the Tay Bridge seems to have a much narrower base.

- Having made the transition, it was decided to manufacture the castings on site at the Wormit foundry.

- The lugs for the ties on the Belah viaduct were on bands attached to the columns, on the Tay they were cast with the columns

- The holes in the lugs were tapered due to casting (resulting in the load being concentrated)

- The tapered hole issue was compounded by using bolts too small for the minimum diameter

- The hold down bolts were too short only penetrated two layers of the masonry base.

The key decision was the need to replace the brick columns with iron, and was driven by the foundation issues, but all the other issues seem to have been driven by cost.

Poor management, supervision and staff selection

In addition to the poor design choices the Inquiry revealed a general slackness in management and supervision, which was ultimately the responsibility of Bouch.

The selection of managers, supervisors and contractors was poor.

- The boring contractor’s failure to determine the true nature of the riverbed. (How competent were they?)

- Gerard Camphuis the Wormit foundry manager had no experience of foundry work. (He had originally been hired to work on the foundations of the bridge)

- Fergus Ferguson the foundry supervisor revealed himself to be incompetent at the Inquiry

- Even the honest and conscientious Henry Noble was placed in a position for which he was not competent.

- The three contractors were the cheapest and we know that Charles de Bergue and Co., were in financial trouble at the time of the owner’s death, due to underpricing their bid.

- The forced change of not one but two contractors is likely to have been detrimental.

Poor manufacturing control

The above staff and contractor choices resulted in and drove poor manufacturing control.

Poor maintenance

Lack of supervision by Bouch and Noble’s lack of knowledge and expertise led to poor and inefficient maintenance, and the inability to identify crucial problems

Final Thought

Bouch may have been the one with the dream, but he had a reputation for cheapness and there were indications from earlier contracts that he was not as attentive as he should have been.

Yet he was hired to build the longest bridge in the world and was also working on the design of the even more ambitious suspension bridge over the river Forth.

So responsibility must finally rest with The North British Railway Company, for lack of judgment and failure to execute sufficient oversight.

What can we as project managers take from this tragedy?

- Do not be overconfident

- Remember your responsibility for end user safety

- If there are major enforced changes, perform detailed risk analysis

- Be aware of the cumulative effect of many small cost savings or changes

- Employ good people, and utilize them appropriately

- Develop a clear handover and maintenance program to ensure safe operation

My Grandfather used to referred to something that had been botched as “A Boucher”. You don’t want your name to be a synonym for a “screw-up”.

Bridge Timeline

Check in next week when we will be talking about “Average” and why it is no longer valid for project managers

NOTES

1The fall of the Tay Bridge: p83-89

2A Lord Provost is similar to a City mayor

3Ibid: p91

4The Tay Bridge Disaster – A reappraisal based on modern analysis methods

5Forensic engineering – A reappraisal of the Tay Bridge Disaster

6The Tay Bridge Disaster Revisited

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- The High Girders: John Prebble (1975)

- The Tay Bridge Disaster – A reappraisal based on modern analysis methods: T. Martin and I.A. MacLeod (1995)

- Engineering Dreams into Disaster – History of the Tay Bridge: Marion K. Pinsdorf (1997)

- Forensic engineering – A reappraisal of the Tay Bridge Disaster: P.R. Lewis and K. Reynolds (2002)

- The Tay Bridge Disaster Revisited: T. Martin and I.A. MacLeod (2004)

- The Fall of the Tay Bridge: David Swinfen (2016)

Another excellent article Jim. Amazing research. Hard to compile so many details in two articles: You did it well.

You should consider converting this to a speech / presentation.

Outstanding, Jim. I really like the timeline.

Thanks Mark

Thanks for the presentation tonight, on this subject, to the PMI Houston, SW Venue attendees. Well done!

Thanks for the support Akin.

Glad you enjoyed it.